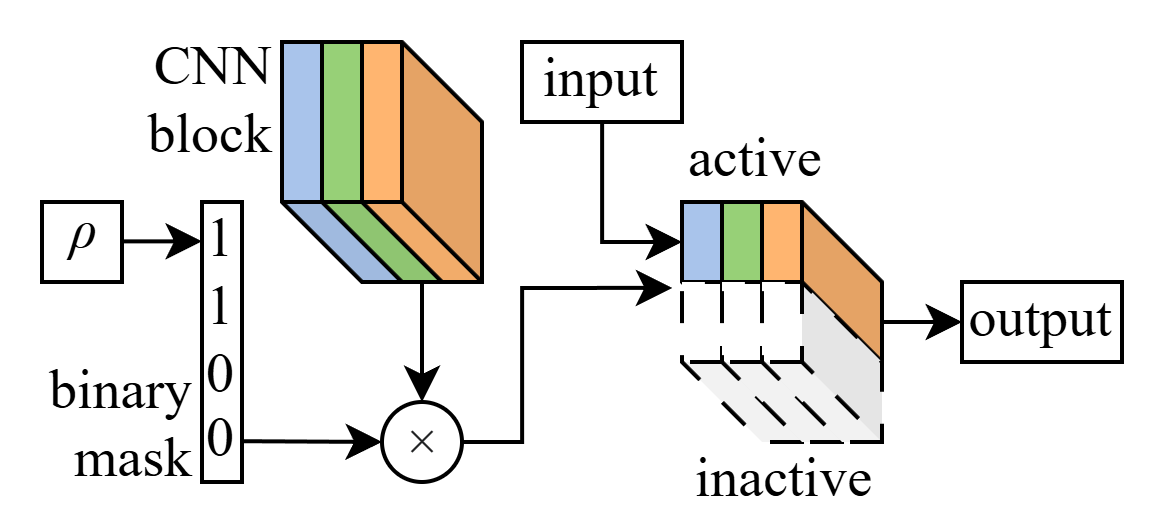

Shown above is a slimmable neural network dynamically activating a sub-network of active channels within a CNN block. Active channels are determined by the slimming factor, , set during a forward pass of a slimmable CNN. In this hypothetical example, and there are four maximum channels.

Dynamic Neural Networks

Common workhorses of my research are neural networks that can dynamically change their structure at runtime (during inference). This is accomplished by adopting architectures that are either multi-branch, allowing for real-time context switching of large neural blocks, or embedded, allowing for finer control of active sub-networks contained within a larger super-network. Specific variants scale neural operations at runtime in terms of: the depth with early exits, the width with slimmable networks, the input sensor modalities, or other sub-structures with more novel approaches.

Autonomous Navigation and Decision Making

Remote tasks such as sensing, science, exploration, delivery, surveillance, and search and rescue, rely on autonomous navigation of drones and rovers through unknown terrain in otherwise hard to reach, or hazardous, environments. Such vehicles are equipped with efficient instruments that have a well balanced information-complexity tradeoff between sensing the nearby environment and the low cost, power, mass and volume requirements of lightweight robotics. Such sensors provide limited information for: navigation, which requires knowledge of the 3D structure of the surrounding environment; and autonomy, which requires various other features to be extracted for downstream control. To this end, I integrate perception-driven modules that process data with deep neural networks into navigation pipelines and autonomy stacks. Further methods such as deep reinforcement learning and diffusion policies offer: flexibility in multimodal inputs and variable decision making, real-time collision avoidance capabilities, and generalizability to unknown environments; while methods such as SLAM and physics based trajectory planning provide precise and less black-box behavior under the assumption that more global information is available.

Shown above is a drone autonomously navigating through an urban environment.

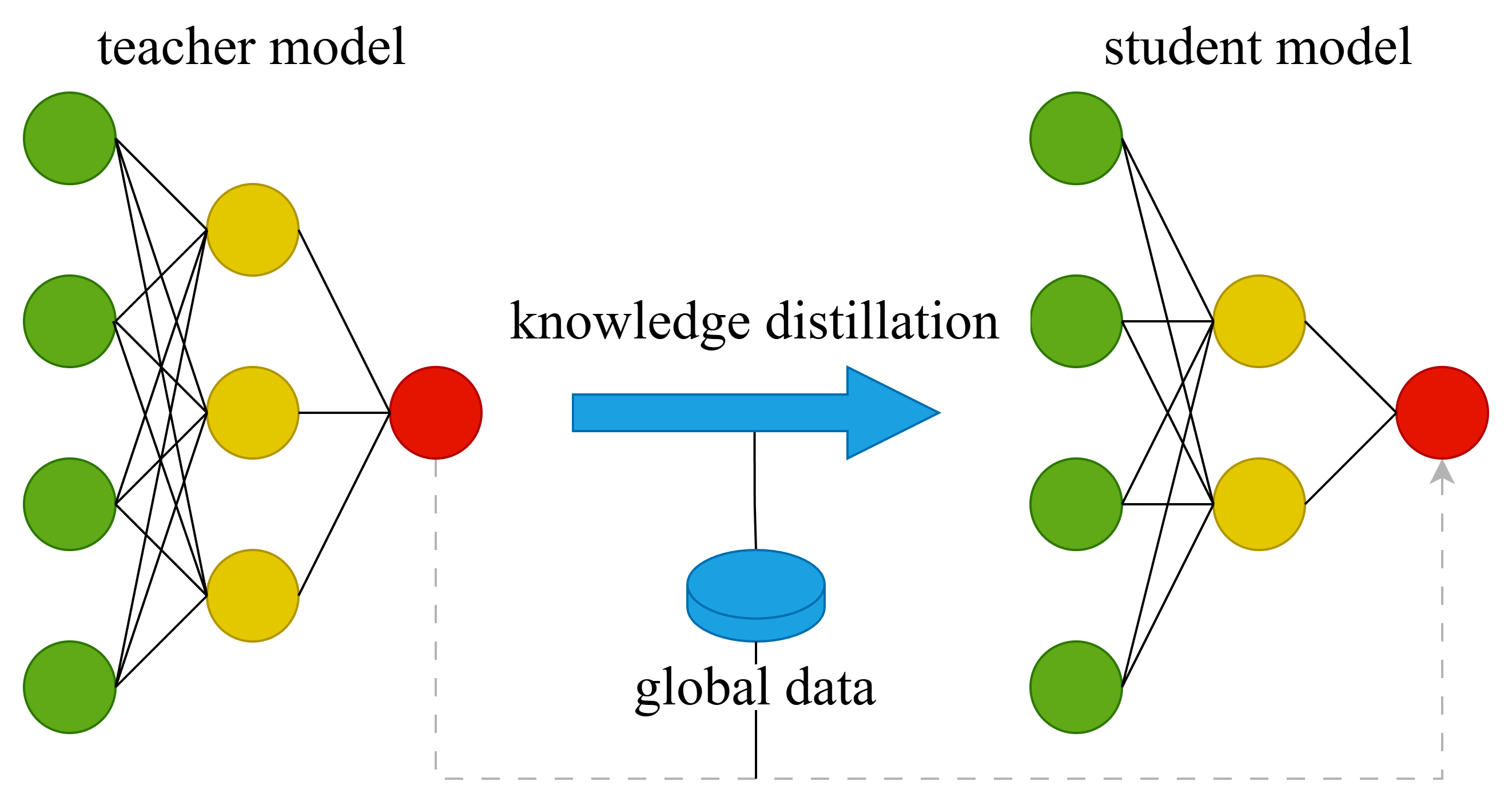

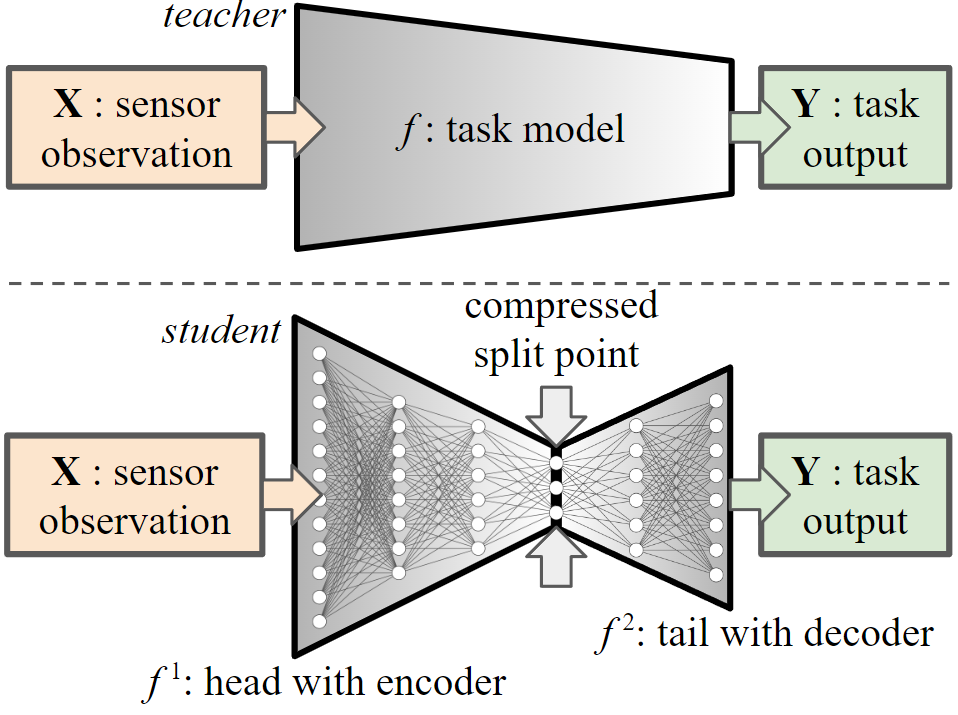

Shown here is knowledge distillation used to reduce the size of a large model.

Model Reduction

Model reduction simplifies deep neural networks so that they can be executed on resource constrained devices, and includes methods such as pruning, quantization, and direct design. These approaches result in neural networks that are static in nature that must be complex enough to handle the most challenging scenarios, and often incur a degradation in task accuracy. Knowledge distillation is a powerful technique that follows a teacher-student paradigm to transfer knowledge learned from a larger teacher model to a smaller student one. This is primarily accomplished using a dual-objective loss function that minimizes: (a) a hard target, which represents the downstream task error, and (b) a soft target, which represents the distillation error between the teacher and student outputs and intermediate latent features.

Adaptive Neural Networks

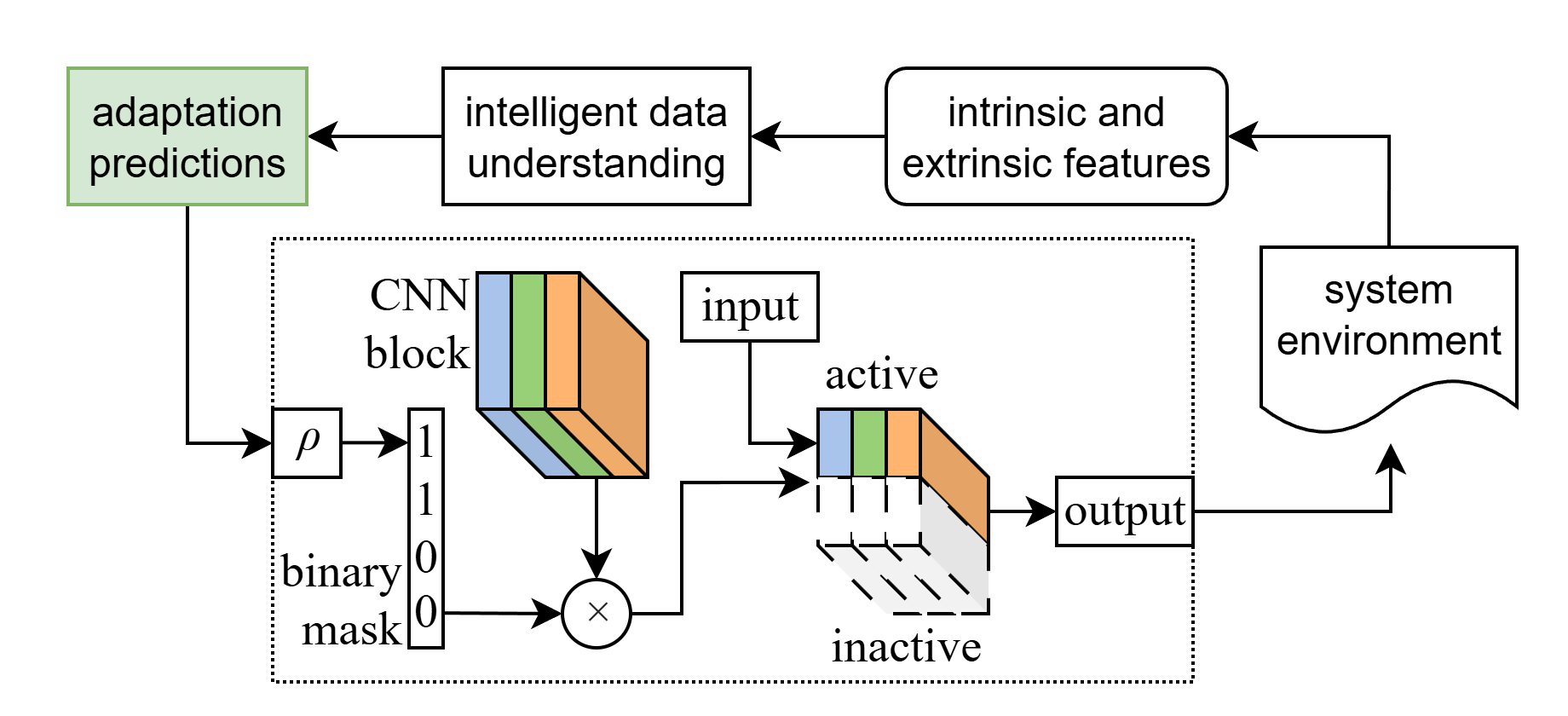

Determining how to optimally activate different components of a dynamic neural network remains an ongoing challenge. The central contribution of my research is the development of adaptive policies that scale the dynamic portions of a neural network in response to contextual cues, environmental conditions, and mission objectives. This approach enables a self-adapting neural architecture that intelligently adjusts its own complexity, improving both efficiency and overall performance. Developing cohesive pipelines that adopt adaptive methods is a significant challenge, and I primarily use deep reinforcement learning which comes with it several other challenges. More details can be found in my research statement.

Shown above is a pipeline in which an adaptive mechanism is integrated into a dynamic CNN block, enabling controlled scaling of the slimmable network.

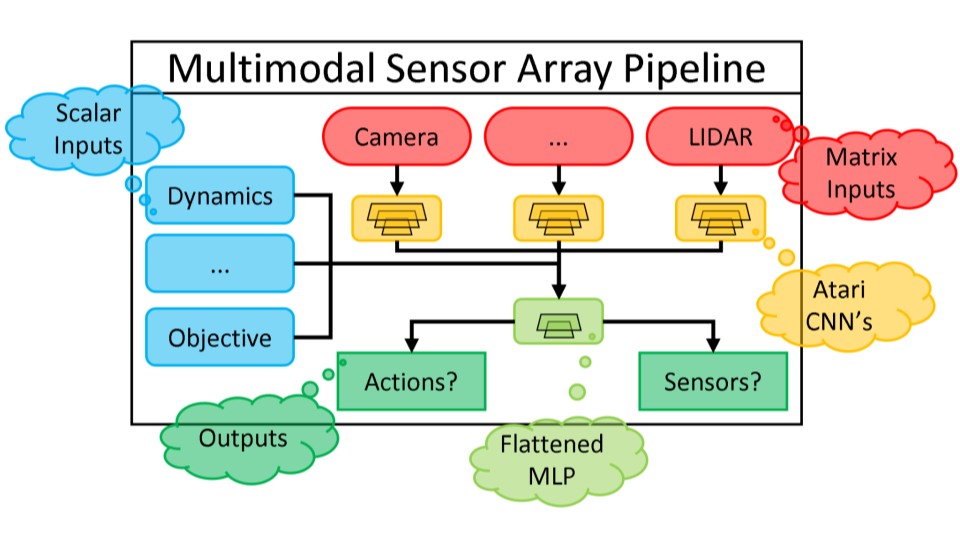

Shown here is a multimodal neural network with a variable sensor array as input.

Multimodal Neural Networks

Real-world data is collected at various time windows, geographic locations, spatial resolutions, and sensing modalities. Such datasets differ not only in their structure, but also in dimensionality, posing significant challenges in developing cohesive data processing pipelines. Various network stems are independently trained, then later joined by mutual neural layers, to integrate heterogenous data types which can be processed and used for downstream tasks.

Edge/Split Computing

Edge computing remotely executes a full deep neural network at a compute-capable device — the edge server. This transmits input data (e.g., images) over volatile and capacity-constrained wireless links, creating problems in efficient channel usage, delay, delay variance, and security. The benefits are that the computational workload for onboard computing is drastically reduced and offloaded to the edge server.

Split computing, also known as split DNN and model partitioning, is a recent class of approaches in mobile computing. DNN architectures are partitioned into two sections — head and tail — that are executed by the mobile device and edge server. The objective is to balance computing load, energy consumption, and channel usage by utilizing supervised compression (w.r.t. downstream tasks) which has been shown to outperform generalized compression.

Shown here is a teacher model injected with a split point used in split computing.

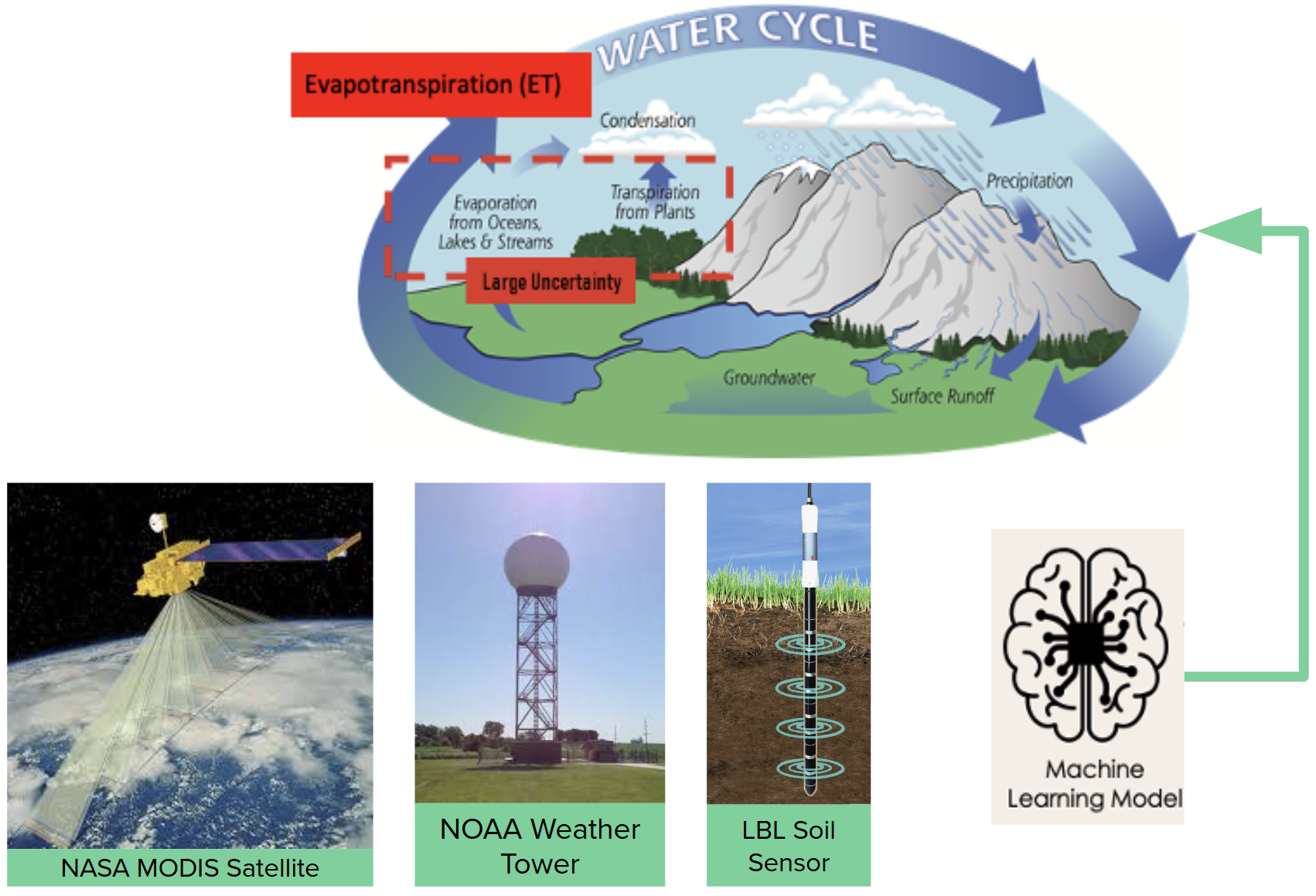

Shown here is a machine learning model using various input sensor modalities as input into a neural network for downstream hydrological studies.

Predicting Evapo-transpiration

Another of my applications is in predicting Evapotranspiration (ET) from real-time satellite imagery, meteorological forcing data, weather towers, and field sensors. Existing approaches typically rely on interpolation methods followed by rigid physics-based calculations. In contrast, I develop flexible DNN frameworks capable of operating directly on noisy, incomplete data by integrating a DAE into the pipeline. These improvements have implications for agricultural monitoring and water-resource management. Further methods can be utilized to determine sensor placement, based on confidence levels and quantified uncertainty.

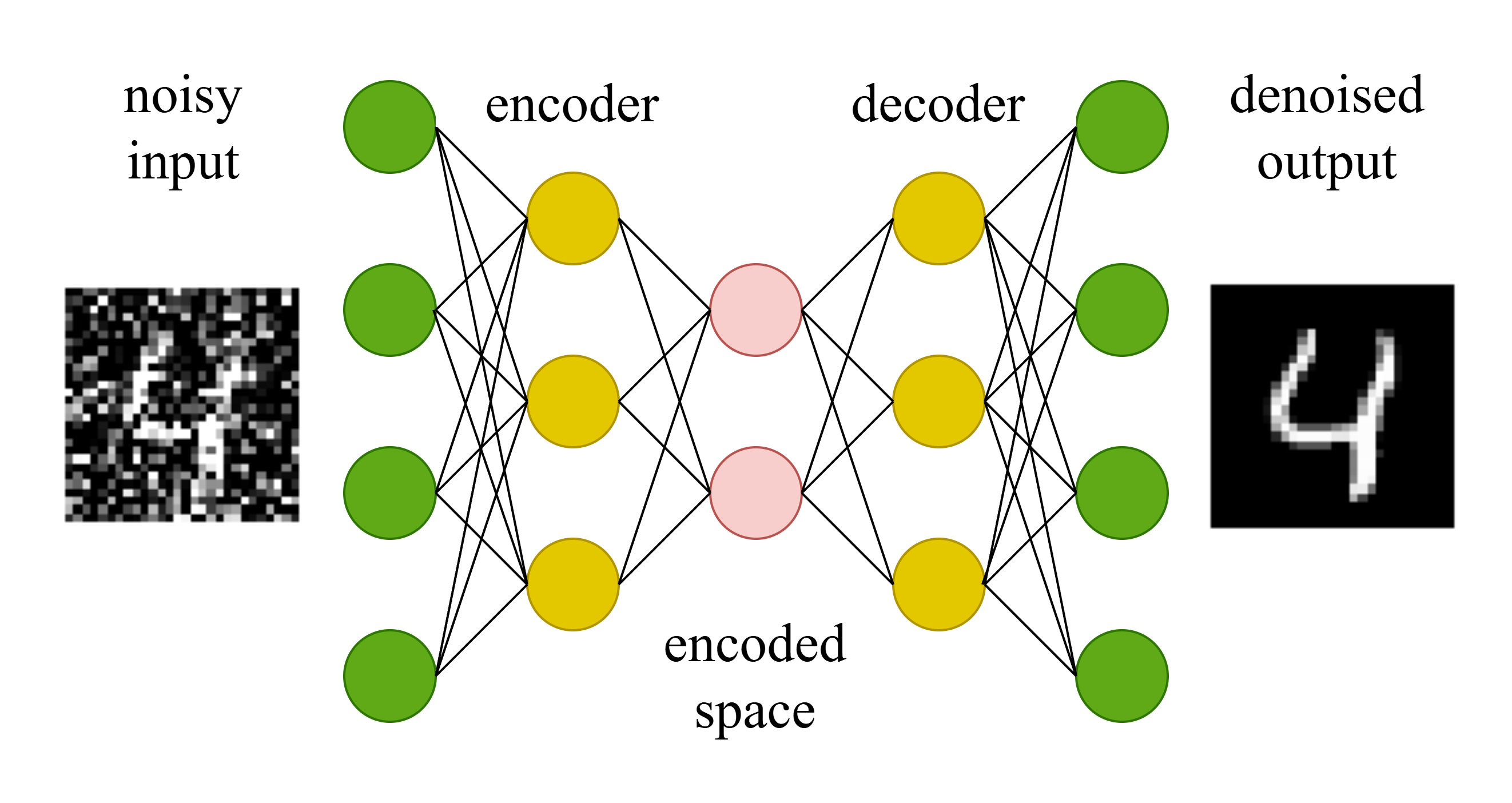

Denoising Autoencoder

A related challenge in real-world data is how to mitigate inherent noise and missing values that result from environmental factors and imperfect sensors. An autoencoder is a neural network that realizes a compressed latent representation of input data. A denoising autoencoder is a derivation that inputs an observation sampled from a corrupted feature space, encodes to a compressed latent space, then decodes to a denoised feature space. The governing principle is that the covariance matrix between the input dimensions is learned during training, so that high signal to noise variables can be leveraged to denoise low ones.

Shown here is a noisy image, from the MNIST dataset which contains hand-drawn numbers, input into a denoising autoencoder that denoises the image.

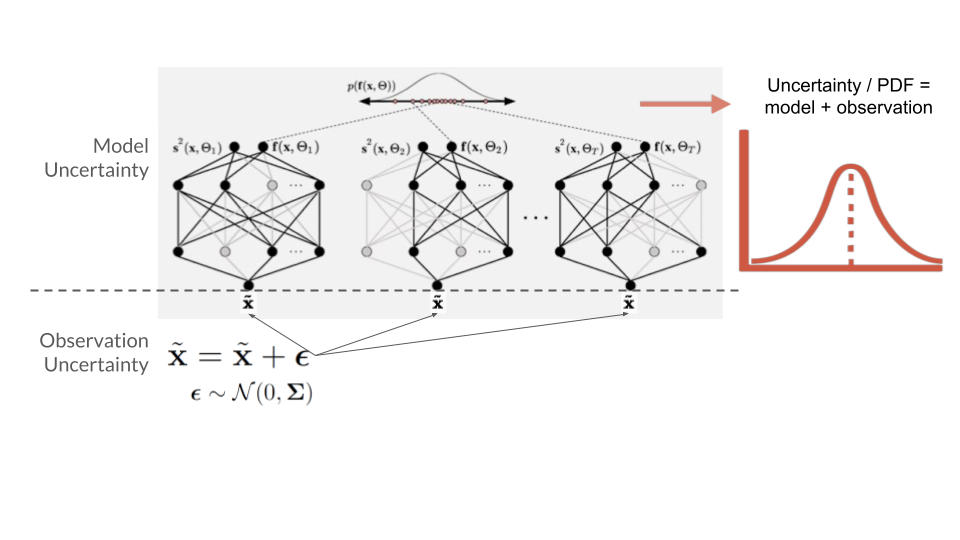

Shown here is a sampling method that perturbs inputs and samples nodes from a neural network used for inferences.

Monte Carlo Sampling

I further advance neural network predictions by integrating Monte Carlo (MC) sampling methods into the inference pipeline for sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification. Classical neural networks produce a single deterministic output, which obscures information about predictive uncertainty. To address this, I introduce random perturbations to the input data to evaluate sensitivity to predictors, and apply random dropout during inference to estimate uncertainty related to model parameters. This produces a distribution of predictions, allowing for an assessment of confidence, variance, and modes. Such information is especially valuable in autonomous surveying systems, where regions of high uncertainty or sensitivity can be targeted for further data collection or more careful analysis.

Mineral Classification

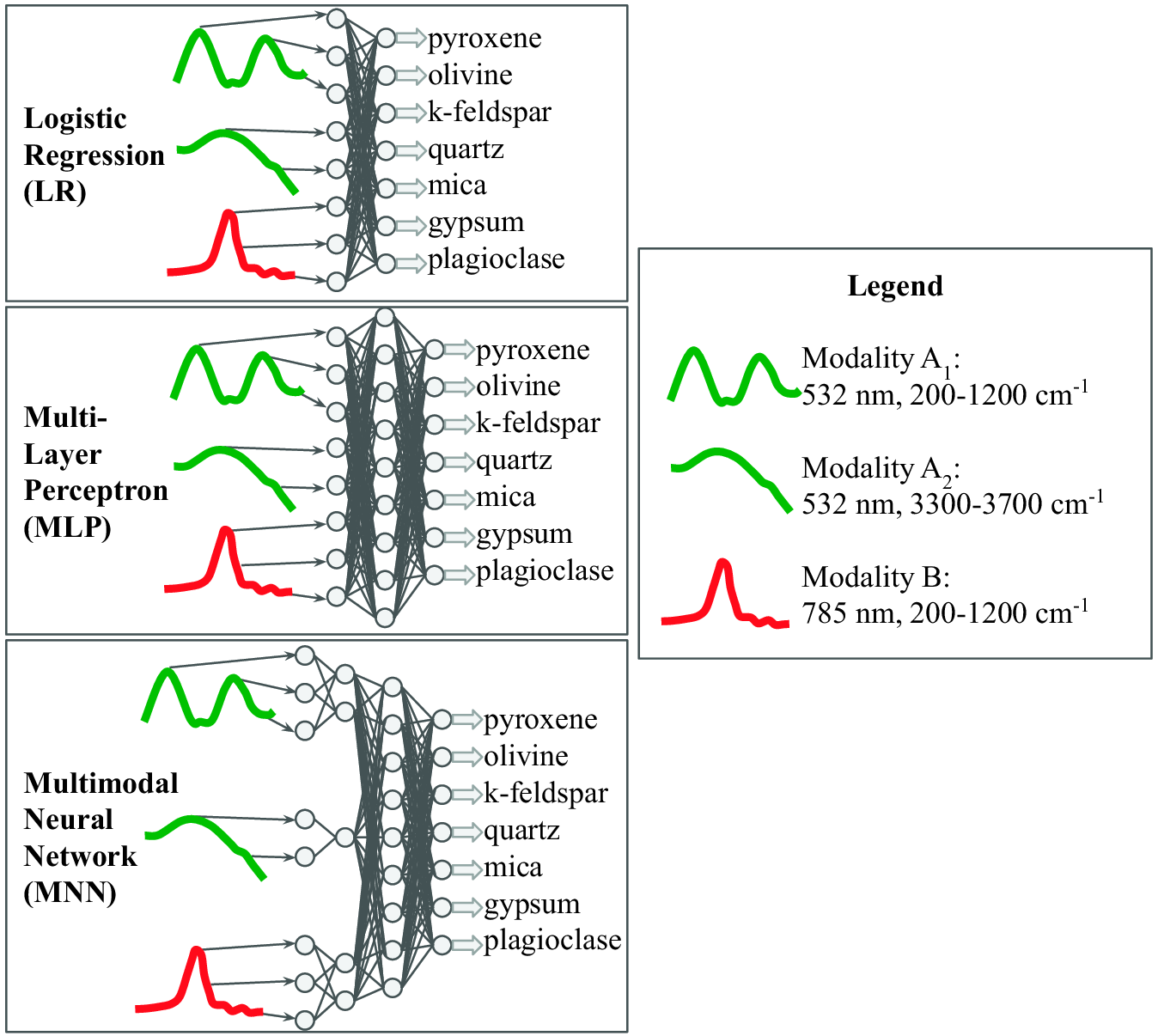

Planetary surface missions have greatly benefitted from intelligent systems capable of semi-autonomous navigation and surveying. However, instruments onboard these missions are not similarly equipped with automated science analysis classifiers onboard rovers, which can further improve scientific yield and autonomy. Such rovers are equipped with scientific instruments including heterogeneous spectrometers and imagers, and typically transmit raw data to an orbiting satellite, which then relays it to scientists on Earth for analysis and further instructions. This process is exposed to severe communication latency and significant resource overhead. Enabling greater autonomy onboard the rover would allow for faster and more efficient in-situ decision making, data processing, and science. To address this issue, I apply my methods to present both single- and multi-mineral autonomous classifiers integrated using the observations from a co-registered dual-band Raman spectrometer, and imagers. I experiment with different neural network structures, showing that a multimodal neural network is the most robust.

Shown above is the progression of more complex methods to integrate different sensor modalities for the downstream task of mineral classification.

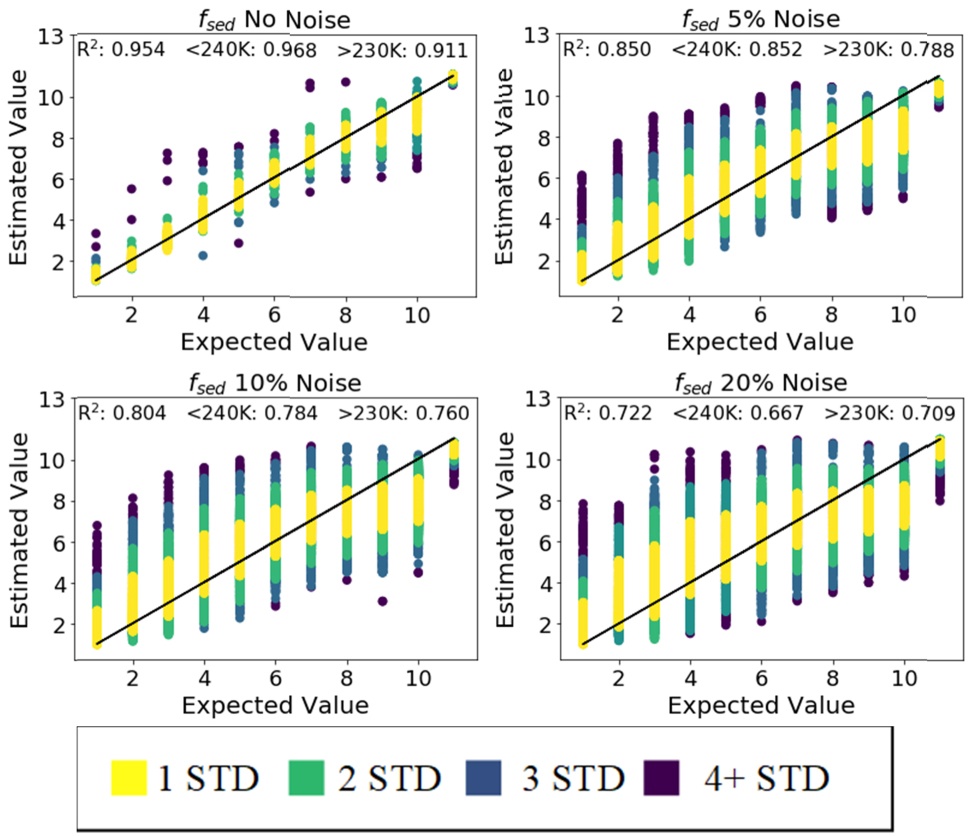

Shown here is the resulting distribution of predictions with four various levels of noise added to the input spectra.

Satellite Development

During the conceptual stages of satellite development, a topic of interest is in assessing whether given mission and instrument design parameters will provide data suitable for extracting quantities of interest. To this end, I developed stand-alone C++ neural network code that potentially helps speed observation and mission design planning, by training a neural network pipeline with the selected mission parameters and evaluating the downstream distribution of predictions. The figure shown here illustrates some results of how the noise resulting from selected parameters for a proposed satellite mission would affect the ability to detect the atmospheric cloud properties, , of exoplanets.